Your longing for hope will be fulfilled

Peter Seal, 17 December 2017

Isaiah 61: 1–4, 8–11; John 1: 6–8, 19–28

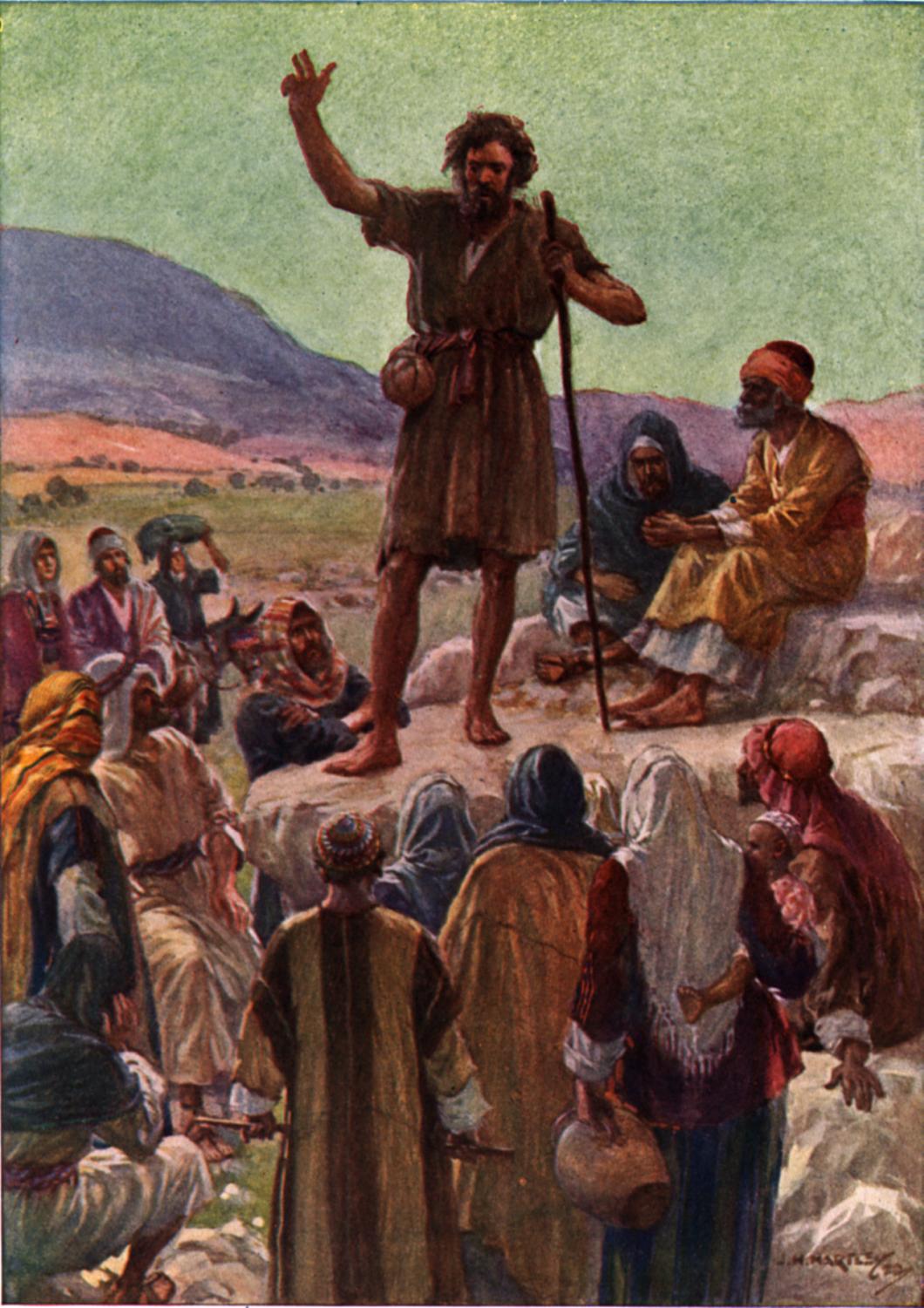

What rich themes this season of Advent gives us: watching, waiting, expectancy. In the midst of this last week before Christmas 2017, the most unlikely figure pushes his way into our lives again.

Yes, of course, it’s John the Baptist. We remember that he’s the son of Elizabeth and Zechariah – he’s Jesus’ cousin, born just three months before Jesus. I want, with you, to try and get inside this gospel reading for today.

We’ll see that John knows exactly what he is and what he is not. He knows that he’s a necessary part of God’s unfolding purposes. He’s the first actor on the stage. He’s the narrator who sets the scene and lets us know what is to come. We can sense a barely suppressed excitement in his voice as he scans the crowd, waiting for the face he knows he – and only he – will recognise.

He understands the job of the herald – both its importance and that it is necessarily transitory. He has no hesitation in applying the words of scripture to himself. He knows that the prophets foretold his coming and longed to see what he is about to see. John gives the impression of being hugely content to be where he is, and what he is.

Focusing on the gospel reading, we note that he was ‘a man sent from God’. He came as a witness, as a messenger. His message is this: ‘The one about whom I’m speaking will bring light, light to wherever it’s needed; indeed, he will be described as “the light”’.

The one about whom I’m speaking will bring light, light to wherever it’s needed; indeed, he will be described as ‘the light’.

The scene is outdoors. We’re at Bethany, beside the River Jordan. There’s a great crowd of people. Suddenly we’re thrust into an unlikely scenario. Sent by the Pharisees, priests and Levites have come from Jerusalem to question John. It has the feel of an open-air courtroom, with a vast number of onlookers. The atmosphere is highly charged. We just don’t know the style of approach or tone of voice the priests and Levites are using. They are, as it were, the prosecutors. Their style, at least to begin with, may have been of gentle enquiry.

Here’s the first question they posed to John: ‘Who are you?’ He knew what was in their minds and replied with a straight, clear answer, ‘I am not the Messiah’. (People claiming to be the Messiah were seen as a threat to peace and good order. The occupying Romans were particularly edgy about those who had the potential to raise up mass movements.)

There follows another question: ‘What then? Are you Elijah?’ (Elijah was expected as the herald to the Messiah.) Again, John gives a straight, clear answer: ‘I am not’.

There follows a third question: ‘Are you the prophet?’ (The return of a great prophet was also expected as a sign of the Messiah’s imminent arrival.) Again, John gives a negative answer: ‘No’.

You can almost feel a growing frustration among the priests and Levites, these senior religious figures from Jerusalem. They ask, ‘Who are you? Let us have an answer for those who sent us.’ And then they add, ‘What do you say about yourself?’ That was a clever way of changing the dynamic – no longer direct questions that can be answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’; instead, what we call an open question.

‘What do you say about yourself?’

I wonder if John paused before answering. I wonder whether he needed to think about how he was going to reply, or whether his self-awareness was so assured that he responded quickly, maybe almost impatiently, ‘I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, “Make straight the way of the Lord”’. By way of a reminder to them that his role was all part of how it was meant to be, he quoted the prophet Isaiah.

The priests and Levites were probably less than reassured by this answer. It hinted that, even if John was not threatening in himself, he was announcing the approach of someone who was!

In fact, John went further. The person he was referring to was already among them in the crowd around him. This response provokes another question from the priests and Levites: ‘Why then are you baptising if you are neither the Messiah, nor Elijah, nor the prophet?’

John answers, ‘I baptise with water’. And then a startling and disturbing revelation for them: ‘Among you stands one you do not know’. And he continues, ‘… the one who is coming after me; I am not worthy to untie the thong of his sandal’.

In his 2004 book Drawn into the Mystery of Jesus through the Gospel of John, the theologian Jean Vanier comments on this passage about John the Baptist: ‘What a beautiful man! What transparency! What humility!’ He continues, ‘If only we could all be like that, not pointing to ourselves and to our own spiritual power, but pointing to Jesus, who draws us to a new and deeper love’.

I think the reason today’s gospel about John rings so true is because we sense in him an authenticity. What you get is what you see or hear. You feel as though his words and deeds form a seamless unity. His words have credibility because they are echoed in his life.

John undoubtedly comes across as humble, but there’s also a real confidence, almost certainty, about who he is and what he’s saying. The genuine humility of John the Baptist is found in his acute self-awareness. This leads him to declare so clearly, ‘Don’t look at me, don’t look at what I’m doing. Look to the one who is to come. It’s in him that your longing for hope will be fulfilled.’

John was a hairy man and he was a prophet for his time. In our age there is another figure, also hairy and also prophetic. I’m speaking of Archbishop Rowan Williams, who is the chairman of the charity Christian Aid.

In his Christmas Appeal – which some of us heard a recording of yesterday evening at our Christmas carols – Rowan encourages us, a little as John the Baptist did, to look beyond ourselves; to look beyond our immediate family and circle of friends. Rowan invites us, compellingly, to give generously to this appeal, which is being matched, pound for pound, by our government. Rowan speaks of hunger as a form of powerlessness and as an example uses South Sudan – a country where many face starvation, a country where famine has been declared.

In conclusion, John the Baptist point us away from himself to Jesus. Archbishop Rowan – on behalf of Christian Aid, and thereby the poorest of the poor – urges us to look beyond ourselves and to give as generously as we can.

Lord God, as we prepare for the birth of your dear Son, Jesus Christ, draw us, we pray, into a new and deeper love.