A transformational journey

Stephen Adam, 23 April 2017

Acts 2: 14a, 22–32; John 20: 19–31

Over the past two weeks we have been on a rollercoaster journey. Through Holy Week we travelled with our Lord to Jerusalem, re-enacting that short-lived triumphal entry to the city on Palm Sunday, through Maundy Thursday as our Lord demonstrated the reality of sacrificial service as he washed the disciples’ feet and commanded them at the Last Supper, ‘Do this in remembrance of me’. We have travelled through the darkness and bleakness of Good Friday to the joy of Easter Eve and the celebration of Easter Day. As we have re-lived these profound events at the heart of our Christian faith, so we have been on a transformational journey, moving from darkness into the most intense, bright light.

And our church, too, has been transformed: from the emptiness of Good Friday to the explosion of colours and scents from our Easter flowers. Most powerful of all is the massed array of lilies in the Lady Chapel at St Paul’s, behind the altar, speaking so powerfully of beauty and remembrance, and perhaps also of fragility and vulnerability.

I would like hold on to this word ‘transformation’ as I offer some reflections on our gospel reading. Earlier in the chapter, John records the first appearance of the risen Jesus, to a woman in a garden – Mary Magdalene. She goes and tells the disciples, ‘I have seen the Lord’, but evidently they don’t comprehend the import of her announcement, for a week later finds them fearful, behind locked doors, scared of what would face them if they ventured out.

And then the risen Jesus appears to them also, transformed – the same Jesus, but no longer confined to space or time. He can no more be kept out of a locked room than he can be confined in a sealed tomb.

His first words are, ‘Peace be with you’. This is no ordinary, polite greeting. Jesus’ first Easter word to his embryonic church is not some pious wish but the concrete fruit of his victory over the grave.

As he shows the wounds in his hands and side so there is a pledge that at the heart of things is redeeming love; nothing less than the harbinger of new creation, the reconciliation of all things. Out of that barbarous killing on the cross comes peace, of a radically different, transformational character.

Out of that barbarous killing on the cross comes peace, of a radically different, transformational character.

And then John records how Jesus breathed upon them, giving them the Holy Spirit and thereby transforming and empowering the disciples for their mission of making Jesus known, commissioning them just as we in the present-day church are commissioned and sent. This is John’s version of the Pentecost story.

John’s gospel is full of the most sublime artistry, and nowhere is this more apparent than here. Take the word ‘breath’ that he uses. In Greek the verb is the same as that used in Genesis when we read of how God formed man from the dust of the earth and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life. We encounter it again in Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones, when God commands breath to animate the bones and give new life.

The language that John uses of Mary encountering the risen Jesus in a garden calls to mind an earlier encounter in a garden, the Garden of Eden. But this is now Eden restored: the second Adam revealing his risen life to the redeemed woman, as Mary Magdalene – the woman with the chaotic lifestyle, who had been possessed by demons – stands for the redeemed Eve.

In the words of Cardinal Newman’s great hymn ‘Praise to the Holiest in the height’:

O loving wisdom of our God!

When all was sin and shame,

a second Adam to the fight

and to the rescue came.

For John, the resurrection of our Lord is interpreted as nothing less than the renewal of creation.

Faithful doubt and doubting faith

And then in our gospel reading we come to Thomas – poor, doubting Thomas who has had such a bad press through the years, forever burdened with the nickname ‘Doubting’. But is he any different from the other disciples, who seemed not to believe Mary’s account and needed to see the risen Jesus before they believed?

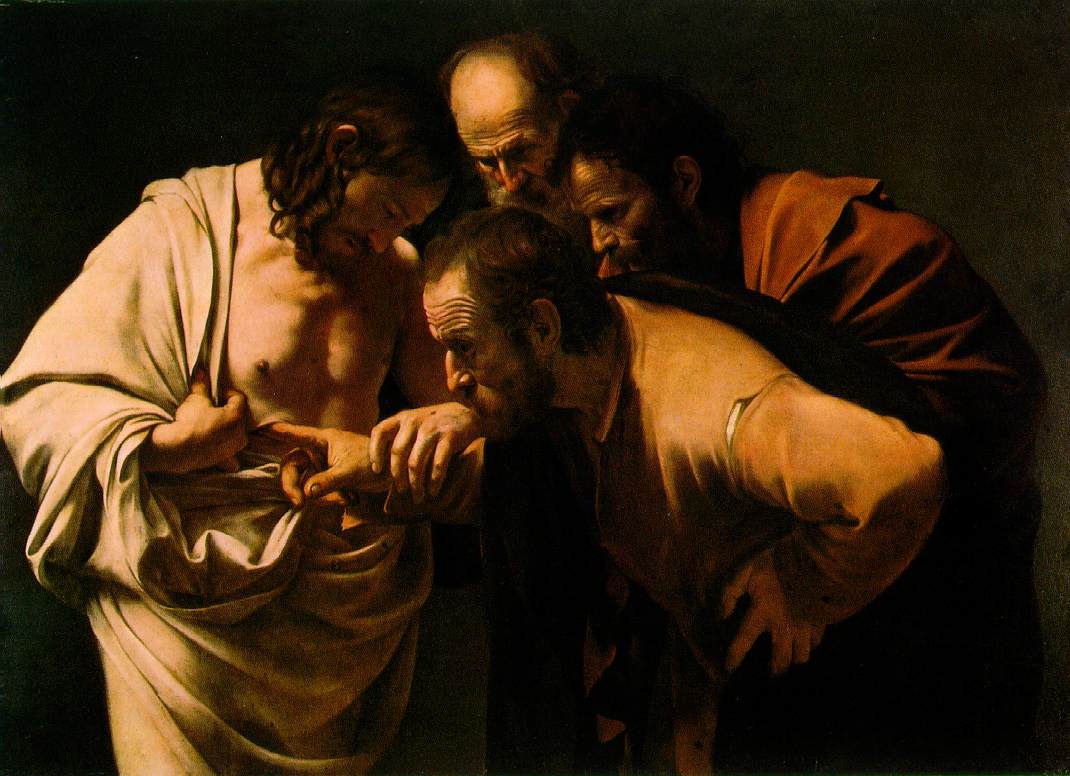

Thomas is honest; he wants to see the evidence for himself. There’s a famous painting by Caravaggio which is almost grotesque, shocking in its crude physicality. Jesus is portrayed not as some otherworldly spiritual body, but realistically – a pallid figure with this gaping wound in his side, inviting Thomas’ fingers to explore.

But Thomas has no need for this – there is no half way house here! He is transformed, and makes the most momentous affirmation in the whole gospel, ‘My Lord and my God!’ In Jesus he has encountered and experienced the Word made flesh, and with that John artfully takes us full circle, back to the words of the prologue to his gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God’.

We are back at the beginning, seeing things with a fresh intensity and understanding; as T. S. Eliot puts it in Four Quartets:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Thomas is known in the gospels as Didymus, ‘the twin’, although we know nothing about his twin or whether he even had one. In a sense it doesn’t matter, perhaps, because he is the twin of each one of us. In Thomas we can recognise our shadow side, our weaknesses – he encapsulates our doubts, our stubbornness, our fears, worries and anxieties. But alongside this was also his loyalty, his courage and his faithfulness.

Thomas invites us to reflect on the nature of our faith. Last Sunday on Easter Day we ended our celebration by singing that rousing hymn ‘Thine be the glory’; we gladly proclaimed our confident belief, ‘No more we doubt Thee, glorious Prince of Life’, and we meant it.

But if we’re honest, I expect most of us also go through times when we struggle and really have to hang on to our faith amid all the buffetings of life and the pain we see in so much of the world around us. Perhaps many of us would echo the famous comment of David Cameron, who described his faith as ‘Like the reception of my local commercial radio station, Chiltern FM: it rather comes and goes’.

We might find ourselves challenged by doctrines that seem far-fetched; we might have moral doubts, wondering how a loving God can seemingly allow suffering in the world; or we might find ourselves simply in the presence of a deep mystery with God beyond understanding, beyond our grasp – that ‘cloud of unknowing’, as it was called by an English medieval mystic. It is this sense of the absence of God, the sheer otherness of God, that permeates the language of another Thomas, the poet R. S. Thomas.

In a recent article, the Very Revd Dr Ian Bradley has argued that, from this perspective, doubt is not the enemy of faith; noisy strident certainty is more dangerous. If you look at Jesus’ own preaching you’ll see he often seems to encourage ambiguity and open-ended questions, using parables, stories and riddles, turning questions back on themselves and wanting his listeners to come to their own conclusions.

Jesus often seems to encourage ambiguity and open-ended questions, using parables, stories and riddles, turning questions back on themselves and wanting his listeners to come to their own conclusions.

Faith can be deepened when we wrestle with ambiguity, when we are forced to question; and Bradley draws attention to a recent book, Faithful Doubt: The Wisdom of Uncertainty, where Guy Collins, a priest in the Episcopal Church of the USA, writes:

Christianity’s worst enemies are not intelligent questioners but those who produce the most noise in proclaiming their trust in Christ. Religious fundamentalism and militant atheism have a number of compelling similarities … Admitting that we do not know much about God should be one of the tenets of orthodox Christian belief. Faith needs to have looked doubt in the eyes and seen its own reflection.

Jesus’ final beatitude can be addressed to us: ‘Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe’. Jesus is affirming that the highest form of faith is that based on trust. I suspect that, for many of us, doubt and faith will always walk together.

But the message that we can take from Easter is that we shouldn’t be afraid, that we should have courage and trust in the risen Lord; that we should open our eyes to the presence of Christ, hear again his words of peace and let the Wounded Healer touch us in our human condition, with all our brokenness, sin and pain; and allow the breath of the Spirit of life to animate us afresh.

May our prayer this morning be that we might be transformed by the joy of the risen Lord, and that this sense of joy, hope and trust might enfold us, no matter what burdens we carry, for ourselves or for our tragic, hurting world. Amen.